- Dr Satish K Kapoor

A recent newspaper report says that Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi- led ISIS has created a separate unit called Khorasan to target the worshippers of the cow.

This obviously raises the question, why do Hindus worship the cow and whether it can be a theological bone of contention?

In a way, the cow is a living heritage not just of Hindus but of mankind. It stands for fertility, prosperity and life, and often called the mother-ancestor, perhaps for being the first mammal to be domesticated by man. She has been mythicized through the course of time and continues to have an aura of holiness and of mystical power, despite being raised as livestock for meat. As has been pointed out by a foreign scholar, during famine, ‘the cow is far more useful as a creature that can produce limitless amount of milk, than as a dead beast that would provide meat for a limited period only.’ In the Norwegian tradition, Audumla, the primordial milch cow fed the six-headed son of Aurgelmir, the progenitor of gigantes.

While the Hindus venerate the cow as mother, the ancient greeks regarded the great cow Europa meaning full moon, as the female parent of stars. In Egyptian mythology, the sky is represented as the divine cow, Ahet, who is mother of the sun itself, the central body of the solar system. A parallel may be drawn with the Rigvedic verse ( X. 85.1) which says that, by Surya are the heavens sustained just as the earth is sustained by Truth.

Another Egyptian goddess, Hathor, who personifies both joy and creation, is likened to the cow, and her image or form used in amulets to ward off evil and to bring good luck. In north-east Africa, along the Nile river, the cow used to be adorned and garlanded or led in celebratory processions as they still do elsewhere, viz. during the harvest festival, Pongal, in Tamil Nadu or the cow festival,Gai Jatra, commemorating the deceased relatives, in Nepal.

Just as the Hindus believe that the cow ferries the souls of the dead across the frightful Vaitarani river mentioned in the Puranas, and goad a dying person to mentally grasp the tail of the cow to attain salvation, the ancient Egyptians used the cow, specially of black colour, in funerary and other rites.

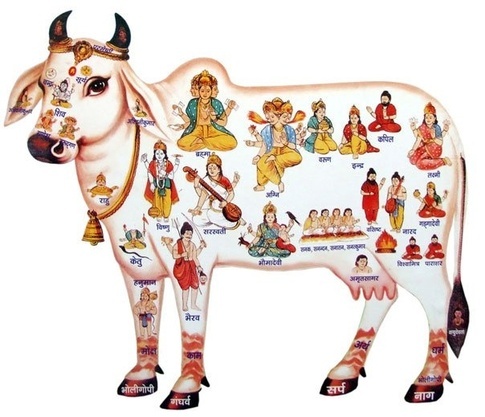

Divinity is locked up in the anatomy of cow as she is said to embody the elements of purity, reality and existence. Her face epitomises innocence – her eyes reflect peace, her horns, royalty and her ears, intelligence. Her udders are the fountain of ambrosia in the form of milk; her tail, a stairway to the higher regions of being. Says the Atharvaveda (X.10):

Worship, O cow to thy tail-hair, and to thy hooves, and to thy form!…

The Vedic Aryans showed great compassion towards animals, and chanted prayers so that their tribe may increase. The Rigveda (VIII. 102.15) likens the cow to be the mother of the cosmic forces, the daughter of the cosmic matter, the sister of cosmic energy, and so on. The cow is Aditi ‘the boundless’, the embodiment of a goddess who supports the universe; her milk and the products made from it are wholesome and nourishing (Rigveda. VI. 28.5). This reminds one of Al Ghazali ( 1058-1111), the Muslim theologian and philosopher, who observed that ‘the meat of a cow is disease, its milk health, and its ghee, medicine. The hymns of the Atharvaveda (IV. 21.1; 3-7) seek bounties of the cow besides praying for their welfare.

The word aghanya -‘not fit to be killed’ – is used 21 times for the cow in the Rigveda, the earliest scripture known to mankind. The idea has a near parallel in the Biblical Book of Isaiah(66.3) which says : ‘He that killeth an ox is as if he slew a man.’

The Yajurveda ( XIII,42,48,49) describes the cow as illustrious and inviolable.

The Manu Smrti (XI. 80) admonishes that if one sacrificed one’s life in defence of the learned men and cows, one became free from the gravest sin.

There may be isolated instances when cows and bulls were used in religious sacrifices but the basic fact is that such practices were abhorred or considered sinful in general. Some Mughal emperors, notably Akbar, are known to have banned cow slaughter. When beef-eating societies were formed in the wake of modernity in mid-19th century India, Syed Nazir Ahmad, a Muslim of Sitapur in U.P., pioneered the cow protection movement by establishing Islami Gorakshan Sabha which became a forerunner of many such Hindu societies.

During the British rule in India, the Kuka Sikhs sacrificed their lives in the cause of cow protection. When the Kuka crusaders,namely, Behla singh, Fateh Singh,Hakim Singh and Lehna Singh, were to be hanged for attacking the butchers of Amritsar on June 14th-15th June, 1871, one of their last wish was that they should not be hanged with leather strings. The widowed mother of youngest martyr, Hakim singh, remarked: ‘Today, I feel blessed because my son has given his life for the sake of the cow,the poor people and the freedom of the country.’

The Great Uprising of 1857 was sparked off by the rumour that greased cartridges to be used by sepoys in the newly introduced Enfield Rifle, were made up of animal fat of pig or cow. During the course of Indian freedom struggle,the issue of cow protection sometime got metamorphosed into national sentiment.

The Hindus worship the cow due to a number of reasons, religious, socio-economic, medical and scientific. Such is the ardour of reverence for the cow that even her dung is turned into a deity during the Govardhan Puja. Pancha-gavya, a mixture of cow’s milk, curd, ghee, urine and dung, is traditionally consumed during religious rites and also used as medicine to have a cleansing effect on the mind and the body.

The urine of cow is said to be a panacea for sciatica, dropsy, jaundice, epilepsy, and other diseases, for which it is taken on an empty stomach; her dung has disinfecting properties and is used for plastering the floor in rural areas. Fumes of cow dung cakes are inhaled in lung-infection,and dung-ash used to cure skin diseases by rubbing, as advised by the German researcher, Monika Jehle. Some Central African tribesmen wash their hands with the cow’s urine and rinse the milking vessel with it for purification.

To Mahatma Gandhi the cow was ‘ä poem of pity’, ‘the purest form of sub-human life’,’the mother to millions of Indian mankind’. ‘Protection of the cow means protection of the whole dumb creation of God’, he wrote. “I worship it and I shall defend its worship against the whole world.’ ( Young India, 6th October 1921; 1st January 1925)

The cow reminds one of Lord Krishna, also called Govinda and Gopala as he

grazed, protected, and nourished cows, of Nachiketa in the Kathopanishad and Prishadhara in the Srimad Bhagavata, of the twelve Alvar saints in Tamil Nadu, of philosophers and mystics like Nimbarakacharya, Madhavacharya, Vallabhacharya and Chaitanya Mahaprabhu, of saint-poets like Mira Bai and Surdas and, in recent times, of Maharishi Swami Dayananda Saraswati, Madan Mohan Malaviya, Vinoba Bhave and others, who held the cow in great reverence, and professed non-killing, as in the Epistle to Romans( 14.20) : ‘For meat, destroy not the work of God.’

India’s national bird, the peacock is beautiful. India’s national animal, Royal Bengal tiger, has strength. But both have little utilitarian value. In comparison, the cow is productive in all respects, and is regarded as a symbol of millennia old Indian culture, emblematic of truth, beauty and goodness – the traits attributed to the cow by the ancient sages.

Dr Satish K Kapoor, a former British Council Scholar and Ex-Registrar of DAV University, Jalandhar is a noted educationist, historian, spiritualist and religion-writer. Infinityami50@gmail.com

South Asian News E-Paper

South Asian News E-Paper Punjabi News E-Paper

Punjabi News E-Paper