Dr.Satish K. Kapoor

Existence hangs on the twin poles of birth and death. But while the occasion of birth is often a matter of celebration, death is looked upon as something horrendous which may shake even the bravest and the wisest.

Man, is on an eternal pilgrimage, moving from the lower planes of consciousness to the higher ones, undergoing one life after another till he attains perfection. Driven by an innate philosophical or existential urge, he is curious to know his fate after he ceases to exist on the physical plane. Death, the cardinal truth of life, has remained the greatest mystery for the common man and the eschatologist alike, who have, through the ages, posed a number of questions. Does the termination of man’s temporal life mean death? Is there any fundamental link between what apparently appears to be dead and what is alive? Is death an end in itself or a stepping stone to better forms of existence? Is there an invisible, eternal self behind the visible, electro-biochemical mechanism, called the human body?

Osho (1931-1990), who reconciled the material with the spiritual, the natural with the supernatural, and the sacred with the profane viewed death not as an ectopic happening – something opaque or abnormal – but as a continuum in an ever-growing, ever-rushing flow of existence. “If birth and death were contrary to each other, how could birth end in death?”, he asked. Death is the culmination of life, its “ultimate blossoming”. The journey and the goal are not set apart. The journey ends in the goal.

Death and life are the two polarities of the same energy, of the same phenomenon. They are not separate or opposites but the very condition of authentic existence. “Life is moving away from the original source. Death is coming back home”. “Life is foreplay, death is orgasmic”. It brings life to a beautiful peak. Life is not just confined to the period that lies between birth and death. On the contrary, “births and deaths are small episodes in the eternity of life”.

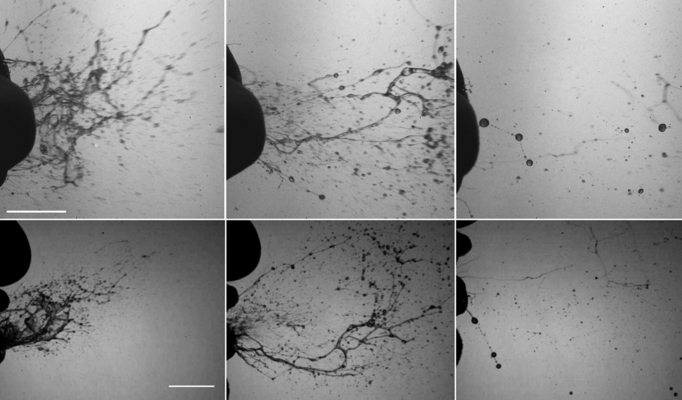

Like Vedantists, Osho regarded man as a wave on the boundless ocean of existence. The wave subsides for the time being only to return in a rejuvenated form. In fact, nothing is born, and nothing ever dies. “Things only move between manifestation and un-manifestation. They become visible; they become invisible”. Human body is like an apparel, and it is not wise for one to identify oneself with it. Nor should one ignore it, or torture it, as the Divine Being is graciously seated inside in full glory. Life and death are both parts of one “greater life”. “That which is beyond goes on using life and death as two wheels of a cart…. It lives through life; it lives through death. Death and life are its processes, like inhalation and exhalation”.

To Osho, Existence is paradoxical – it exists in opposites. The course of life is dialectical, and one may find opposites complementing and supplementing one another. “Life exists only though death – that is the paradox. And one can become a conqueror only by surrendering – that is the paradox. One can have only by losing – that is the paradox. And one can be full only when one is empty – that is the paradox”. This comes closest to the Taoist vision of Chuang Tzu who saw adversity and prosperity, security and danger, growth and decay as a part of the process of “reverse evolution” which unites opposites. The world, believe the Taoists, has come out of the “unrealised potentiality” of the Tao, and it is the fountain of the active power (Te) in “all that has being”. Says the Tao Te Ching (XVI, XL):

“All things come into existence,

And thence we see them return

Look at the things that have been flourishing;

Each goes back to its origin.

Returning is the motion of the Tao….”

Osho was no recluse who would reject life or be indifferent to the visible phenomenon, like Lao Tan (6th century B.C.E.), who justified inaction by saying that the Tao takes its own course irrespective of what we do. Rather, he argued, that it was not possible to understand death without understanding life, in all its phases and aspects. But life could not be grasped through some dogma or philosophy. There was no way to know life “expect by living it”, “being alive”, by “flowing” or “streaming with it”. Life is not a “thing” but a “process”, a “wandering”, not a “home”. It is not anywhere in the future but here-now. None can guide another into the meaning and purpose of life; the explanation will have to come from within. Life consists “in adventure, in constant enquiry and exploration”. Unlike plants and animals whose life is somewhat pre-programmed, man with his self-consciousness, reflective thinking, ability to discriminate between good and evil, and having the power to rise above his milieu, can choose to become a devil or an angel.

The apparent diversity in life was seen by Osho as “the notes of great symphony”. Like Epicureans, he said that “life is the only truth there is”. But at the same time he regarded matter and spirit as the two sides of all existent things. “Matter is the outer side of spirit, spirit is the inner side of matter. They are not separate….Hence a right vision, a total vision of life will be a synthesis, a synchronicity between matter and consciousness”. Osho saw the principle of polarity behind creation. God, the divine architect of life, had put “the bricks of birth and death together”, facing each other. “Think of the world where death does not exist. Life will not be there eternally, because if death does not exist, life will simply disappear”.

To Osho, life was “non-Aristotelian” and “non-Euclidian”. Hence it dodged persons who lived in the glasshouses of ideology. Life could be grasped only when one was ready to delve into the unknown realms of existence. “If you cling to the known, you cling to the mind and the mind is not life. Life is non-mental, non-intellectual, because life is total. Your totality has to be involved in it.”

Like the classical Buddhist thinkers, notably Acharya Nagarjuna (C150-250C.E.) Osho believed that even though death was an unavoidable feature of existence, it caused distress only to those who tried to evade it, in one form or the other.

The question arises, if life and death were the two ends of a continuum, called existence, why did people fear death? Was it instinctive or the consequence of faulty perceptions injected by religions or sects into the minds of human beings? Osho blamed “pseudo-religions” for propagating a negative view of death, for presenting it as the arch rival of living beings, and for keeping an anti-life attitude. He agreed with Francis Bacon that men fear death as children fear to go in the dark; and as that natural fear in children is increased with tales, so is the other.

Fear is auto-psychotic as it stems from a desire to cling to the outer self. All forms of fear are just echoes of the most fundamental fear – that of death. When we see someone dying, we are in a state of trepidation as “each death reminds us of our own death”. We are not participants in that grim experience yet we feel shaken. What do we observe – that the “dead” man is no longer breathing; that his heart beats no more; that his body is undergoing decay. “But do you think all these things put together are equivalent to life?” he asks. “Is life only breathing? Is life only heartbeat, the blood circulating and keeping the body warm? If this is life, it is not worth the game.” There is obviously something more to it than is ordinarily felt or perceived.

“God! Is there anything uglier than frightened man”? asked Jean Anouilh (1910-1987), the celebrated French playwright. Unfortunately, fear is embedded in the collective psyche of mankind, and it manifests itself in myriad forms. Osho ruefully noted that man had structured his life out of the fear of death. “The fear of death has created society, the nation, family and friends. The fear of death has caused us to chase money…. And the biggest surprise is that our gods and our temples have also been raised out of the fear of death.” It was this fear which was exploited by the priestly classes and others for their selfish ends. Taking a dig at his own countrymen, Osho said: “This country of ours talks untiringly about the immortality of the soul, and yet is there anyone more scared of death than us… Is it ever possible for people who believe in this principle to become slaves? They would rather die…. Because they know there is no death. Those who know that life is eternal…. would be the first to land on the moon…. to climb Mount Everest…. to explore the depths of the Pacific Ocean! But no, we are not among those…. In fact we are so scared of death that…. we go on repeating: ‘The soul is immortal.’ Nothing becomes true by repetition.”

Death is intertwined with life in much the same manner as the seed with the tree. The seed ought to die if it has to unfold its potential. The body is the shell; the spirit is the kernel. In death, the two are separated. Man fails to realise that he existed even before his birth, and that he will continue to exist even after he is physically no more – in some other form, with some other form, with some other label.

The influence of the Vedanta philosophy is clearly discernible in Osho’s view of life and death, even though he moulds it, and often mixes it up with the perceptions of Zen monks, Jewish mystics, Bauls, Vaishnavas and Taoists. Who is afraid of death in You? He asked. Obviously, life is not because how it can be apprehensive of “its own integral process”? “It is the ego which is afraid in you. Life and death are not opposites; ego and death are opposites. Ego is both against life and death.”

Osho’s view that death should be an occasion for celebration may look quixotic at the outset. But a deeper study of it is likely to change our opinion. If at all we regard death, as most of us do, as a return to the primordial source of existence, or as Herman Hess put it, going into the collective unconscious and losing oneself in order to be transformed into purer form, there

can be no reason to feel anguished. ”No death is death; because every death opens a new door – it is a beginning, a resurrection”.

TO BE CONTINUED

South Asian News E-Paper

South Asian News E-Paper Punjabi News E-Paper

Punjabi News E-Paper